Make Congress Blue Again Facebook Banner

O north the morning of 28 October last year, the day of Iceland's parliamentary elections, Heiðdís Lilja Magnúsdóttir, a lawyer living in a small town in the due north of the land, opened Facebook on her laptop. At the height of her newsfeed, where friends' recent posts would usually appear, was a box highlighted in low-cal blue. On the left of the box was a push button, similar in style to the familiar thumb of the "like" button, but here it was a mitt putting a election in a slot. "Today is Election Twenty-four hours!" was the accompanying exclamation, in English. And underneath: "Find out where to vote, and share that you voted." Nether that was smaller print saying that 61 people had already voted. Heiðdís took a screenshot and posted it on her own Facebook profile feed, request: "I'1000 a little curious! Did everyone get this message in their newsfeed this morning?"

In Reykjavik, 120 miles south, Elfa Ýr Gylfadóttir glanced at her phone and saw Heiðdís'southward post. Elfa is managing director of the Icelandic Media Commission, and Heiðdís's boss. The Media Committee regulates, for example, age ratings for movies and video games, and is a role of Iceland's Ministry building of Education. Elfa wondered why she hadn't received the same voting message. She asked her husband to check his feed, and there was the button. Elfa was alarmed. Why wasn't it being shown to everyone? Might it accept something to do with different users' political attitudes? Was everything right and proper with this election?

Iceland had just reached the end of its most arduous and dirty campaign flavour ever. For weeks, anonymous accounts had been spreading accusations on social media about near every political candidate. The state had been flooded with bizarre "exposé" videos on Facebook and YouTube. Some had been viewed millions of times, fifty-fifty though Iceland has but around 340,000 residents. And now this push. Was there a connectedness?

Elfa watched as more and more than people responded to Heiðdís'south postal service. Some had seen the push, others had non. Out and well-nigh on election day, Elfa asked everyone she met most information technology. Information technology was clear that non anybody had received the message. Of those that did, some got information technology later than others. Some had seen it while scrolling through their Facebook newsfeeds; for others information technology appeared at the top. Meanwhile, responses to Heiðdís's post appeared to prove that users given the push option were non randomly selected either. Minors and non-citizens were not shown it: just those in the voting population. Just then, every bit she was also discovering, non all of them. Was there some kind of blueprint?

Immediately later on the elections were over, the push disappeared. In that location was no sign of it on Facebook'south company site Newsroom or on any government sites. Elfa rang a friend, Kristín Edwald, chair of the Icelandic Ballot Committee. Edwald was totally surprised; she had never heard nigh this push. Not even the special commission, given the job of working on an update to the election police force, knew what Elfa was talking about.

Elfa had an idea why none of the authorities had taken the push button seriously: at start glance, Facebook'south get-out-the-vote button seems harmless. What event could a uncomplicated ballot twenty-four hours reminder possibly have?

The Icelandic elections are simply the almost recent time the button has been employed for major elections in the west. In the US, it was starting time used – and fully disclosed past Facebook – in 2008, and over again in 2010 and 2012. Facebook has published its own studies about its effects. Initially, despite some scepticism on the left, it was mostly seen as a positive tool, bringing people to the ballot. Facebook was an emerging phenomenon, with a couple of hundred million users.

The offset known cases of the button beingness used exterior the US are the Scottish referendum in 2014, the Irish gaelic referendum in 2015 and the Uk election after that year, all of which were communicated by Facebook. After that at that place was silence nigh the button – and no further public statements past Facebook. Only the company has now revealed, in answer to questions in the preparation of this article, that the push was used in the U.k. in the 2016 European Union plebiscite, the 2016 Us presidential election that brought Trump to power, and in Germany's 2017 federal elections.

Merely what effect did information technology accept? That we don't know. And if Facebook does, information technology'due south not saying. Did its button make a deviation in crucial, closely fought contempo elections? In the Eu referendum in Britain or the election of Trump in the Us?

In the ongoing debate nearly the influence of Facebook on politics, the bug largely revolve effectually third-party applications. The crucial distinction about the vote button is that it is fabricated and operated past Facebook lone: this is Facebook itself becoming a political role player. Indeed, in his testimony to the United states of america Congress, Facebook primary Mark Zuckerberg proudly cited the apply of the push button during the last US presidential election.

And this was what concerned Elfa in Iceland. The primary reason for her worries was a presentation she had seen two weeks before the Icelandic elections, at a conference of the Council of Europe and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in Vienna. Information technology had been part of an OECD panel on false news, Russian manipulation online and personalised ad. At the middle of the thing was abuse of social networks by third parties. The button, notwithstanding, was something else entirely. It was Facebook'due south very own tool. And, in contrast to all the speculation effectually the bodily effects of fake news, Facebook had numbers.

The presentation had been given by the Austrian digital ambassador to the EU, Ingrid Brodnig. Brodnig had spoken about i of the largest e'er experiments in the field of social science. It had taken place on the day of the 2010 U.s. congressional elections, when Facebook suddenly sent a voting reminder to 61 million US users – a quarter of the United states voting population. Every US Facebook user over the age of 18 who logged in on election twenty-four hours saw the message. Then a team from Facebook, together with researchers from the University of California at San Diego, weighed Facebook datasets confronting election returns. The goal was to discover out whether the "voter button" actually got out the vote.

The results of the report were published in September 2012 in the periodical Nature. The decision: the button works. Users who saw information technology were more likely to vote. The result was slight, but scaleable in the millions at only the cost of a line of code. It made the button the almost effective voter activation tool ever built, creating 340,000 additional voters. It was possible, concluded the researchers, that "more of the 0.6% growth in turnout betwixt 2006 and 2010 might have been caused by a single message on Facebook".

If Facebook had shown the button to every Usa voter, more than a million voters could have been mobilised. This was the showtime scientific evidence of the real influence that the still-new network could have – an important message for Facebook'south potential advertising customers. Elfa heard all of this for the first time at that conference in Vienna. The Austrian digital ambassador ended her spoken communication by saying: "There has never before been so much power in the hands of a single company."

In 2012, Facebook once over again tested its capacity for influence. This time in the United states presidential elections. It was announced on Newsroom that all users would be shown the push (which turned out non to be the example). The results were published (past Facebook – there was no independent report) in April 2017 in the science journal Plos One. The button had worked once again: 270,000 additional votes were bandage.

For users who got both the button as well as notifications from friends who had voted, the rise in participation was 0.24% this time. As slim as that seems, in 2000 George W Bush beat his presidential opponent Al Gore in the decisive state of Florida past 537 votes. That's 0.01%.

On US election day in 2012, media reports indicate that Facebook did other tests to optimise the button. Even today not much is known about them. Facebook has never revealed publicly how many variations of the button they tested. But the company apparently wanted to know which worked better: when Facebook simply displayed the button or when it came as a recommendation from a friend.

This was the reason only some people saw the election day reminder at the top of their newsfeeds while others saw it equally a post shared by a friend. Some people saw the push just at their computers, others saw it on all devices (a Facebook projection managing director at the time, Antonio Martínez, says that in 2012 he heard from co-workers that developers were undecided whether to testify the button on iPhones: that alone could bias election results, they worried, because iPhone users tended to be more urban and liberal). There were multiple variations in the text; some read "I'm a voter", while others came up "I voted".

The primal questions are: how much of a difference does it make when Facebook turns on its button? And could Facebook potentially distort election results simply by increasing voter participation among only a certain group of voters – namely, Facebook users? At its cadre, Facebook is an ongoing experiment being conducted on order. In Facebook'south optics, we are all the subjects of a global experiment in profit-maximisation. No one tin predict precisely what the effects of a certain program amending will be, so everything is constantly being tested.

Facebook can see in great detail how we react to every unmarried alteration they make. The Facebook algorithm that's ever being talked almost does not exist. It's more than accurate to say there are many continuously-under-evolution programmatic threads that interact to make up one's mind what comes upwardly in our individual Facebook feeds. The aim is ever to increase "engagement" – the time nosotros spend interacting with the platform. For our part, we notice that we are beingness experimented on just about as much as rats in a maze exercise.

Merely once has Facebook apologised for an experiment: in 2014 it was revealed that information technology had tested 689,003 users to determine how much their feelings could be influenced. During the "emotional contamination" experiment for one exam group, positive posts from friends were partially withheld; for the other group, negative ones. Even if the effects were slight, Facebook showed itself to be a sort of thermostat, with which the moods of its users could be regulated. The very thought of information technology: a company which, in order to test its product, risks the psychological wellbeing of its users – this created an uproar. But one thing Facebook learned from the backlash was that it was better keeping things secret.

When something problematic does go revealed, Facebook turns to the same arguments: it'due south the mistake of ill-intentioned, careless or clueless users. In the case of Cambridge Analytica, Facebook showtime blamed the users whose information had been misused for being unable to comprehend its terms of use policy. Then they cast Cambridge Analytica every bit the villains who had taken advantage of user ignorance. Facebook is always the victim, never the culprit.

The Facebook employee who first exported the "voter button" outside the U.s.a. is the London-based Californian Elizabeth Linder. She is 34, a Princeton graduate and was an early recruit at Facebook, starting in 2008 (she left in April 2016). In an upmarket vegan restaurant in central London, she relates how she built upwardly Facebook's "global politics and regime outreach" department. Working from her London office, her job was to persuade the political classes of Europe, the Centre East and Africa that Facebook was the place where voters were – and that, therefore, politics has to be there too. At first it was crude going. "The politicians all thought Facebook was just something for young people," she said.

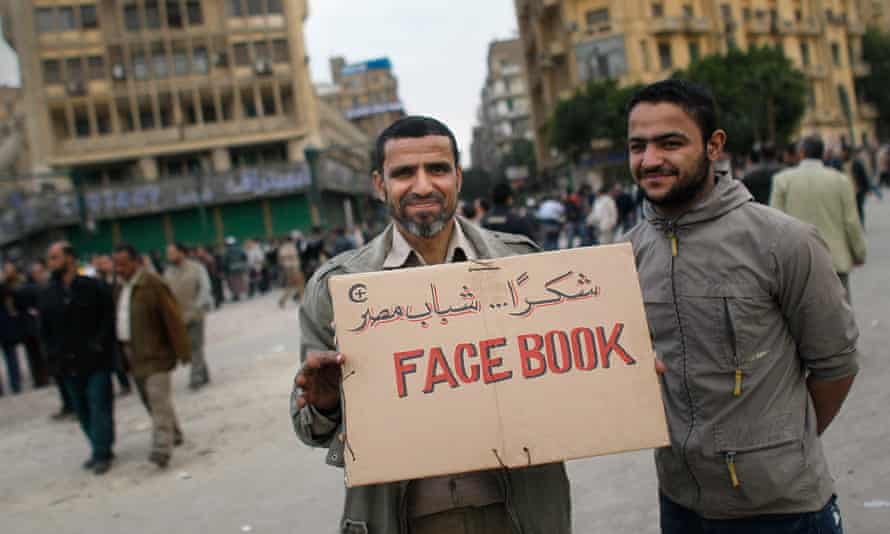

So came the Arab spring. Immature activists used Facebook to network, spread their ideas and organise demonstrations. Governments in north Africa were toppled. The Arab spring was the all-time marketing for Facebook ever. It turned a toy into a tool of power. Politicians and government officials from all over were busy trying to contact Facebook, and it was Linder they spoke to. She has advised the Vatican and British parliament; she brought the Dutch imperial family unit on to Facebook. She says she spent the eve of the 2nd Tahrir uprising with the social media section of the then Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi. She had one articulate aim: "Fulfilling our mission to make the world a better place." In Macedonia, she advised pro-Europe organisations; in Lithuania, Radio Free Europe; in Uganda, women's groups.

"The first fourth dimension I used the 'voter button' was in Scotland," says Linder. "That was 2014, the independence referendum." She doesn't see anything wrong with the button. It is an excellent reputation marker, something that proves the impact of Facebook, she says. "The argument I used to convince Facebook [to extend use of the button globally]," says Linder, "was the whole affair about the push really having an impact on voter participation in America, and how we could achieve the aforementioned bear upon internationally." After all, by then seventy% of Facebook users lived outside the US. The button wasn't some business concern scheme, says Linder. Yous tin't make coin with it.

Did Facebook have a bigger plan? She says not. Were at that place concerns almost potential political influence? Only occasionally. One case she mentions is Lebanon, where she avoided giving political consultation, not wanting to accidentally advise people who could exist on a terrorist watchlist. Who determined when the button should exist deployed? Her alone, Linder says. The Scottish independence referendum was, in her view, a expert place to start: only two camps, similar to the Us. "The second i, I think, was a referendum in Ireland." And so the 2015 elections in Britain. The long-term goal was to utilise the button in "every major ballot". In Britain in 2015, Facebook made an endeavor to communicate it, did a lot of marketing. Later, they wouldn't.

And yet there is indeed 1 public announcement of Facebook's plans to implement the "voter push button" worldwide, from 2014. At that fourth dimension, the project was publicly well received. Since then, however, Facebook has been silent on the matter. At that place is no information or any accounting bachelor about where the button has been deployed, except for i announcement in Bharat.

Searches for the button on the cyberspace yield private screenshots posted from many places, including India, Colombia, Kingdom of the netherlands, Ireland, Hong Kong, South Africa – even from the European parliamentary elections. Also represented are countries in hard geopolitical environments, such as South Korea and Israel, and endangered democracies such as the Philippines, Turkey and Republic of hungary.

What remains unclear most the button – this powerful tool that a United states corporation can insert into elections globally completely free of public scrutiny – is when and why it gets deployed. Practise you accept to pay to have it activated? Or is it enough simply to take a cordial relationship with a Facebook employee?

"As far equally I know, at that place is no public list of where the 'voter push button' has been used," says Linder. And within the company? "Yep."

She left Facebook in 2016. Why? "I wanted to stay in Europe," she says simply. When pressed, she shrugs. It had always been her dream to live in London. And, no, she has never been to Iceland.

When I approached Facebook to ask why they had used the push button in Iceland, a public relations house replied: "We show a message on election day to remind people to vote." Its explanation for the button not being shown to every user had to exercise with users' individual notification settings or their utilise of an older version of the app. Every bit to how strongly voter participation had been influenced in Iceland, there was no comment. Nor did Facebook say who was actually shown the button and who was not. That information is "unfortunately" not bachelor "for whatsoever state". The list of countries in which the push button had been used could not be provided either.

Why doesn't the company desire to reveal this information? To what extent has the push influenced election results in recent years? What political data is being gathered? Are models beingness tested and strengthened? Voter participation in Republic of iceland turned out to be surprisingly high. There were increases amongst both young and erstwhile, even though experts had been speaking before the poll of a general sense of election burnout. Whether this was due to the button, and who benefited most from the additional votes, is impossible to tell without more information from Facebook.

Facebook is a U.s. company without an function in Iceland. In a certain way, its use of the push constitutes interference by a foreign actor. Facebook has meddled in the democratic elections of a foreign country, and no one outside of the company seems to know anything almost it. Replies to inquiries with Iceland's justice ministry building, election committee and intelligence services indicate that they were ignorant on the bailiwick. Fifty-fifty Páll Þórhallsson, the chief legal counsel to the prime minister and an internationally experienced media lawyer, had non been informed. Simply the deployment of the button was probably not illegal under Icelandic police. Legislators could hardly accept predicted these kinds of methods, then why formulate whatsoever legal text to encompass them?

Facebook had sent a squad to Iceland, on 10 October 2017, just xviii days before the election. In a parliamentary coming together room – accessible only with a laissez passer – two representatives, Anika Geisel of Facebook'southward politics and government outreach team and Janne Elvelid, the company'south Stockholm rep, had been meeting leaders from the major parties. They had given a ii-hour introduction on the ways politicians could engage on Facebook with potential voters – what they could achieve with the platform, how they could maximise the "engagement" of their fans. The examples they showed were in German. Facebook cited the page of Sahra Wagenknecht, of Germany's far-left party die Linke, every bit well as the fan page of then soon-to-be Austrian chancellor Sebastian Kurz, as examples of "all-time practices". It was a standard promotional presentation, with examples pulled from the Austrian and German elections – the slides were in German.

But why was Facebook in the country at all? The tips their team gave were banal. The presentation left most visitors wondering why the coming together had been held – there was no mention of paying Facebook or of advertising opportunities. Nor were there any answers given to the pressing questions on who was behind the moving ridge of faux news videos that had flooded the land. The "voter button" wasn't mentioned. Facebook had been invited by the conservative Independence party, which declined to annotate for this article. Elfa, who speaks Swedish, decided to e-mail Janne Elvelid. At beginning he responded warmly but when she sent him questions most the button, he suddenly had no more time for written communications. She should call him, he said.

And then on eight February this year she did call him. He had been assigned to Iceland, he told her. He had discussed deploying the "push" beforehand, by phone, with someone in Iceland'south justice ministry. Facebook had sent the push button to every user, he said. Still, Facebook tin't really tell who actually sees the button; algorithms and user settings would ultimately decide that. Facebook cannot control who deactivates which notifications.

In statement after argument, Facebook insists it supports democracy. But in Iceland, after six elections in one decade, with confidence in the political system shaking, and when democracy needs nothing more than badly than trust, Elfa was left with cypher but doubt.

The experiment is still going on. Early concluding calendar month, an acquaintance sent Elfa a screenshot from the elections in Italian republic. The button showed upwardly there likewise. In response to my questions, Facebook stated that information technology had also deployed the push in the concluding federal and regional elections in Germany besides as for the Brexit referendum.

In Iceland, outrage about Facebook is beginning to mount. Meetings are existence held, including with MPs and the prime minister'due south part. Elfa is still wondering why Facebook is investing energy in introducing its button all over the world. The only caption that makes sense to her is that elections help to bring people to the platform; that users, every bit soon every bit they see that their friends voted, will take their political battles to Facebook, and, with their increased engagement, help Facebook bring in more advertisement. That would be the turn a profit. The cost is borne by democracy.

This is an edited, translated version of an commodity that first appeared in Das Magazin in Switzerland. The translation was past Edward Sutton

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/apr/15/facebook-says-it-voter-button-is-good-for-turn-but-should-the-tech-giant-be-nudging-us-at-all

0 Response to "Make Congress Blue Again Facebook Banner"

Postar um comentário